The hardest season yet

Documenting this year's exceptionally violent olive harvest in the West Bank.

Last year, I wrote that 730 Palestinians had been murdered in the West Bank since October 2023. A year later, 1,001 Palestinians have been killed, one in five of whom were children. The horrors witnessed during the 2025 olive harvest season feels like the inevitable consequence of these past years, in which settler impunity and unbridled military oppression have deepened their roots.

As I write this, the olive harvest in the West Bank is drawing to a close, the last olives remain on their branches, and those that did make it to the press have done so in defiance of severe, targeted violence. After a year of drought and a severely reduced olive yield, state-backed settler militias sought to deepen the hardship, launching relentless attacks and stealing olives from Palestinian farmers. The following reflections come from my notes during this year’s harvest, which I participated in as a member of Rabbis for Human Rights, an organisation that for over two decades has coordinated Israeli and international volunteers to stand with Palestinian farmers, providing a protective presence in the face of settler violence and military occupation.

On the first day of the harvest we travelled to Husan, a Palestinian town trapped inside the seam zone between the Green Line and the apartheid wall. We were helping a farmer whose family’s trees hadn’t been harvested for years. The effort to harvest on these lands served the dual purpose of gathering their crop as well as fighting a legal mechanism that Israel relies on to seize land. Under a dusty Ottoman-era law, if a tree is left untended for three consecutive years, the land it stands on can be reclassified as “state land”. The olives themselves seemed secondary to the imperative of holding onto their land.

We had barely arrived when three soldiers stormed toward us, one with a military patch depicting the third temple, another with one that read “Messiah Now!”. They told us we were threatening the security of the settlement, Beitar Illit, which looms over the village. Submitting to this unjust order, we harvested olives further away from the settlement, succeeding for an hour before being presented with a closed military zone order, a long-standing tactic the IDF uses to disperse Palestinians and activists alike from an area they arbitrarily decide should be out of bounds. Within minutes the landowner received a fine and a threat: if he dared return to this land again with volunteers, they would block his entry to Battir, a nearby village where he owns a successful business. His economic life was held hostage because he sought to pick olives on his private land, with the assistance of non-violent, mostly Israeli, volunteers.

By the end of the day, the soldiers had herded us back to Husan’s entrance, where a yellow gate had been shut. Almost 10,000 Palestinians were locked inside their village, blocking any movement in and out. It’s a scene familiar across the West Bank; over 850 of these yellow gates can be found ghettoising Palestinians in their towns, villages, and cities. What made this moment surreal were the Haredi men, likely from Beitar Illit, buying goods from Palestinians through the bars of the gate, engaged in commerce with people who were, at that very moment, imprisoned at the will of a soldier. I wondered if the settlers of Beitar considered their paralleled realities.

The next day brought us to Deyr Ammar’, where dozens of Palestinians gathered hoping to reach land they hadn’t accessed in years due to a settler outpost built on the hill above their terraces. The outpost was home to a handful of settler youth – but it takes only a handful to render this land inaccessible. When we arrived, the army was already there waiting, ready to present us with yet another closed military zone order.

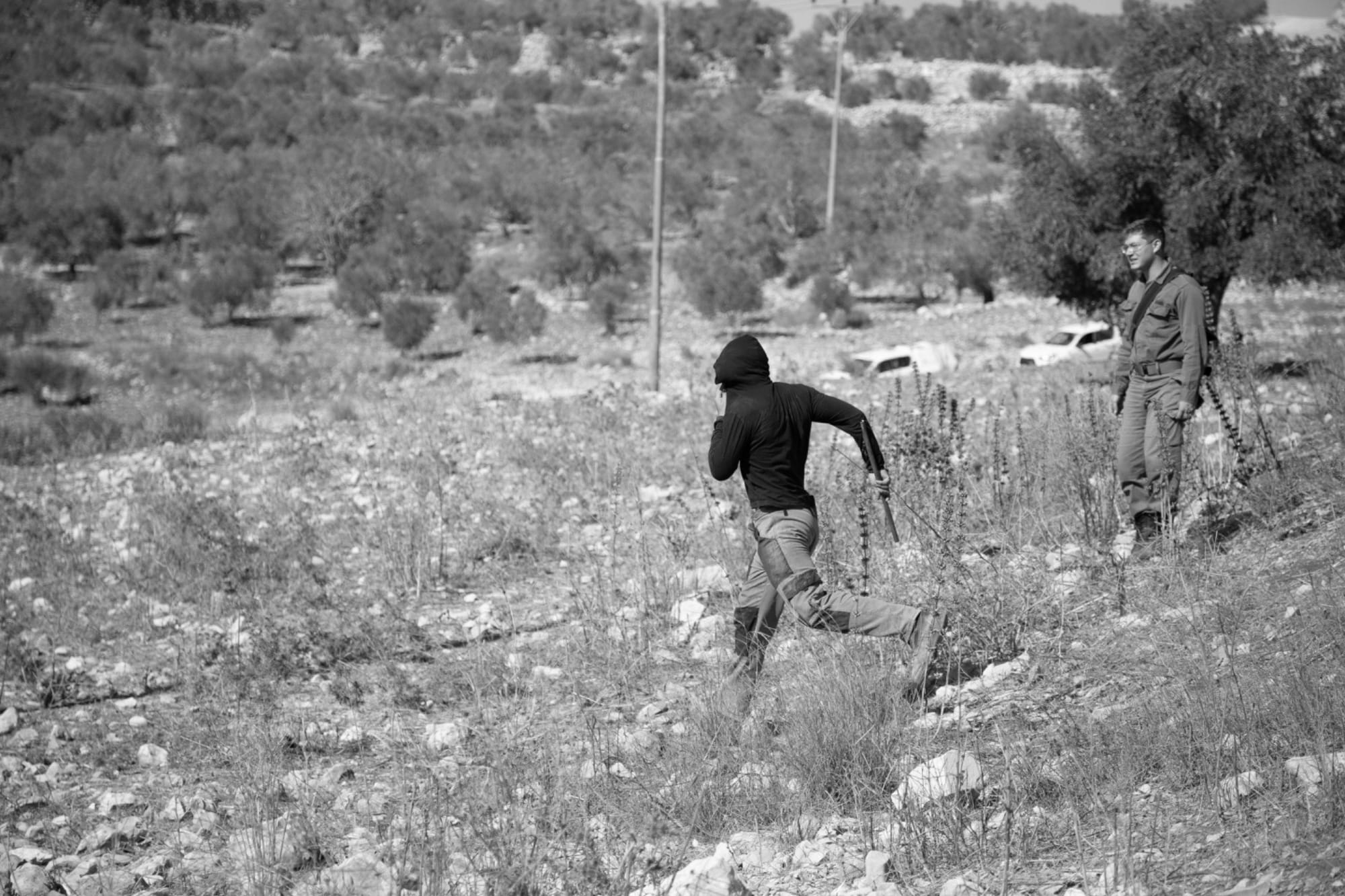

Thirty meters up a hill, soldiers hurled sound grenades at a group of Palestinians who had been denied access to their land near the outpost. Then came settlers running down the hill, some carrying wooden sticks (the sticks they use to herd their flocks through Palestinian land are the same sticks they beat Palestinians with). Others were throwing boulders at us. Further below, a separate group of settlers attacked four Palestinians who had managed to begin harvesting. One man was struck in the head and taken to hospital.

Not a single settler was arrested, and we picked almost no olives that day. Out of the thirty harvest days Rabbis for Human Rights joined farmers, over a third were shut down by closed military zone orders, alongside four “movement restricting” orders, blocking activists from even entering the West Bank. This became the drill. The bureaucracy of the occupation is as efficient as it is cruel.

This year’s harvest was also marked by full-blown pogroms at a higher frequency than usual. The violence did not stay confined to the groves, spilling into villages and Bedouin communities. Major attacks would often fall on Shabbat – on 17 November, the village of Jaba saw a pogrom in which scores of settlers set fire to homes and vehicles, attacking residents and spraying racist and genocidal slogans on buildings and walls. A similar incident had happened in Mukhmas on 25 October, in which homes on the outskirts of the village were burnt to ashes. We visited the remains days after the attack, which left a Palestinian resident and two Israeli activists hospitalised for days. Smoke was still rising from one home which I have stayed in many times while doing protective presence shifts.

In the middle of the harvest, I was barred from entering the West Bank for fifteen days. This happened on the same day that two American volunteers – both Jewish – were deported to the US. I can’t write much about that day because I was made to sign an oath by the police, swearing not to speak publicly about the case; the occupation is terrified of cameras, solidarity, and anyone who might document what settlers and soldiers do in the olive groves and beyond. That I was forced into silence demonstrates the state’s fear of witnesses.

The relentless attacks, the bureaucratic machinery, the roadblocks, the outposts, the fines, the orders: they all work together toward pushing Palestinians off their land and establishing an on-the-ground reality of a single Jewish state between the river and the sea.

Throughout these months, I saw Palestinian farmers return again and again to groves from which they had been pushed and expelled. I saw volunteers risk assault and deportation simply to help Palestinians families pick olives and exercise their right to remain on their lands. But I also saw courage that far outweighs the cruelty we faced. Our responsibility is our presence. We cannot stop standing with Palestinians living under occupation and surrounded by state-backed militias. If these trees are to remain under the care of their rightful guardians, they will need witnesses who refuse to accept their destruction as normal.▼

Author

Jacob Lazarus is a photographer and filmmaker working on long-form documentary projects surrounding modes of resistance in Israel and Palestine.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.