The embarrassing acrobatics of the Reform Jewish Alliance

A Jew joining an anti-migrant party sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. If only there were something to laugh about.

I was shocked by the creation of the Reform Jewish Alliance. Maybe that was naïve. Launched in a room of 200 people at London’s Central Synagogue last Tuesday, the organisation exists, in its own words, “to mobilise members of the Jewish community to vote and back Reform while ensuring Jewish Britons’ interests are represented at the highest levels of the party.” In his speech at the event, Nigel Farage reportedly said he had been moved to set up the group after meeting the family of British-Israeli hostage Emily Damari and feeling that other politicians cared too little about her return. He also said that the group would help the party target up to fifteen parliamentary seats.

In retrospect, one of the reasons I was shocked was actually a reason not to be. The RJA’s emergence follows months of reports about Farage’s alleged schoolboy antisemitism, including his apparent habit for wandering up to classmates and “growling” “Hitler was right” and “gas them”. Farage has denied the accusations, calling them politically-motivated “fantasies”; regardless of their factuality, it was inevitable that some more overt effort was going to be made to counter the image they create. What was less obvious to me was that certain Jewish figures and institutions would be so willing to help.

I suppose that was the real cause of the shock. Before trying to prove itself anti-racist, Reform had been busy proving itself a collective of scuzzy opportunists, and its pre-existing reputation – cultivated and accidental – for being the party that does and says things other parties won’t do and say leaves limited room for surprise. But as I sat there watching clips from the launch, which featured the blurred, momentary heads and shoulders of a roomful of people who had gone along earnestly, I thought: what would make a Jew – a group so conscious of its minority status, one that tells holy stories about escaping persecution and historical ones about its consequences – join Reform?

Israel is one answer. Farage has also announced the creation of Reform Friends of Israel, while he’s previously expressed enthusiasm for Trump’s Gaza Riviera and criticised Labour’s decision to block (most) weapons export licences. If all you want is a pro-Israel British party, though, you have a range from which to pick. This choice of name, when there is already a Conservative Friends of Israel, a Liberal Democrat Friends of Israel, and a Labour Friends of Israel, actually struck me as a clumsy tumble into the mainstream for the “disruptor” party. Maybe that’s the point: to signal, in this case, the same steady support Britain reliably shows, and attract the kind of support those groups have enjoyed in turn. (Labour, for its movements, was still willing to undermine terror law to defend Elbit factory roofs.) Any onlooker, too, should be able to tell that Reform’s support for Israel has less to do with it being Jewish and more to do with its approach to “undesirables” on territory to which it believes itself entitled by historical and/or divine decree.

More of RJA’s backing, I think, is explained by a domestic phenomenon: the fear of Muslims – and therefore of Middle Eastern and North African migrants to Britain, who are often Muslim – being cultivated in British Jews. Partly this is just as it’s being cultivated in other groups, on the basis of perceived scarcity. Jews are not, as we left-wingers often point out, a monolith, and some are probably as convinced as others by the misattribution of blame for too few school places and NHS GP appointments. And partly it’s different, because it has that relationship to Israel and Palestine and to a history that is wider and more complex still.

Obviously that history involves animosity. Obviously there are cases of antisemitism among Muslims in Britain, including cases that result in serious tragedy such as the Manchester synagogue attack. But there has also been an effort by individuals inside and outside Britain’s Jewish population to turn anxiety about the worst cases and about Israel and Palestine into a general suspicion – by, for example, characterising marches with a large Muslim contingent, demanding the protection of largely Muslim lives, as “hate marches” (and erasing their Jewish contingent entirely), or through more brazen references to “Islamic bloodlust” and claims that the concept of Islamophobia is “bogus” cover for anti-Jewish feeling.

Policy-wise, Reform UK is concerned with migrants specifically, not Muslims in general, although representatives have been involved in scandals, and the internal abuse directed at its now-Spokesman for Home Affairs, Zia Yusuf, suggests that some of its supporters might take a certain position. For elements of the far-right, like the people who attacked mosques and hotels housing migrants as part of the same round of riots two years ago – riots in which some believed Nigel Farage’s Twitter activity to be a factor – migrants and Muslims collapse together as categories into a single “un-British” mass.

The relatively small and innocuous Jewish community, with certain of its leaders and publications speaking out against the danger this mass supposedly poses, is cast in these circumstances as a “model minority”, one willing to aid the national defence. The ultimate emptiness of this characterisation, beyond indicating political usefulness, was evidenced at the RJA launch when Alan Mendoza reportedly lamented that other groups have failed to assimilate to “British values” (the way, this line suggests, Jews have), after which Farage said “Judeo-Christian values” had shaped what Britain is today.

Which came first, the British values or the Jewish ones? This is one of several near-halachic problems the RJA and its ideology seem to pose – and yet there were bodies on those chairs. It would be comforting to think of RJA members simply as Reform’s useful idiots. But Farage’s pluralist schtick vividly exposes the calculation at play: the decision to accept gangsterish promises of specialised protection for Jewish people in exchange for assistance in the effort to demonise elsewhere.

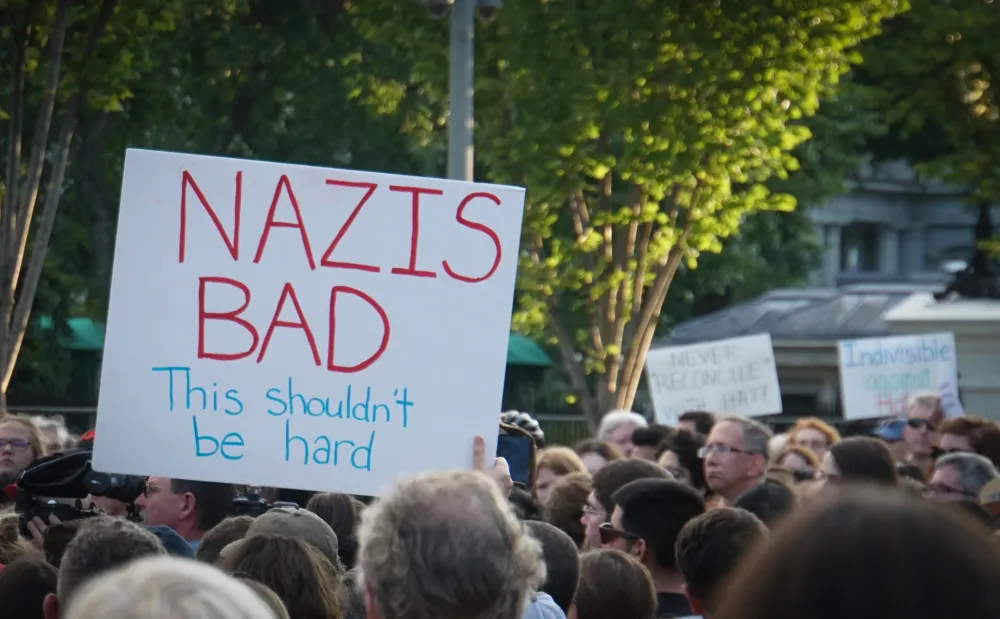

Thankfully, others had a more productive reaction than shock. A group of Na’amod members interrupted Farage’s speech at the launch to point out the insult the event represented to the descendants of Cable Street fighters – and to the Torah, with its invocation to welcome the stranger. This week, one of their number, Josh Cohen, spoke on LBC Radio about the cold reception that late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Jewish migrants – many fleeing pogroms – received in Britain, and the fact that Britain’s first peacetime anti-immigrant act, the Aliens Act of 1905, was intended to limit the intake of Ashkenazim.

The aftermath of the shock is fatigue. This is it in a new, more brazen form, but the effort to rewrite the history of Britain’s Jewish community, to erase the fact that we were also once called invaders, is familiar by now, as are the necessary retorts. Sometimes I feel a little embarrassed by writing them out again. I suppose I’m thankful to those 200 attendees at Central Synagogue for comforting me on that front, because nothing is as embarrassing as being in the RJA.▼

Author

Francesca Newton is assistant editor at Tribune and an editor at Vashti. She currently lives in Melbourne.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.