A voice for some

The Board of Deputies frames itself as the voice of Britain's whole Jewish community. Its archives tell a more complex tale.

On 15 April this year, a letter to the Financial Times started a controversy in the Board of Deputies and the British Jewish community more widely. The letter, signed by 36 deputies, spoke out against Israel’s current actions in Gaza. Five of the 36 were promptly dismissed by the Board, which also issued a statement denouncing the letter. In the statement, the Board’s president, Phil Rosenberg, claimed to be speaking on behalf of the majority of British Jews. “I am confident that the vast majority of Deputies and the Jewish community as a whole agree with me,” he wrote. It was a strident claim – and the latest addition to a long struggle over the question of British Jewish representation.

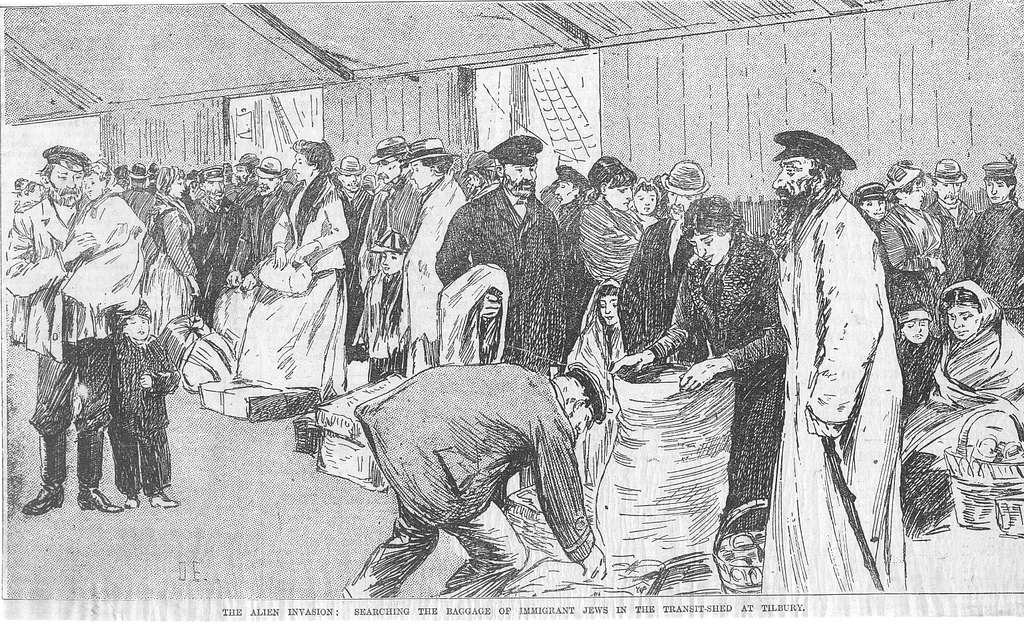

The Board’s commitment to its status as the representative body of British Jewry has been questionable since at least the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That period saw a surge of Jewish immigration from eastern Europe, one that forms the backbone of the Jewish demographic in the UK today. Alongside this mass migration came a rise in antisemitism, which soon became embedded at an institutional level. In this context, the small elite of Jews who had come to run the Board of Deputies since its formation in 1760 formed a vital lifeline for newcomers.

But the Board was not interested in trying to represent the Jews who lived in this country. Looking through the Board’s deposits at the London Archives, as I did recently, it becomes clear that it was focused instead on trying to portray a particular image of Jewishness to the wider public. In this effort, the Board saw the new wave of immigrant Jews as disagreeable partners. These Jews could not speak English, were still committed to Orthodox religion, and brought with them distinctly “alien” practices.

To the Board, these habits were not just different, but deficient. Even in a 1904 publication entitled In Defence of the Alien Immigrant, which pushed back on some parts of the Aliens Bill (itself designed specifically to block Jewish immigration), the Board felt the need to admit that “criminality among the foreigners generally in this country is greater than that among the native population”. Rather than representation, the Board set its focus on Anglicisation, a process that ended up largely destroying the culture the immigrants had brought with them.

One of the Board’s main targets in this process was Yiddish-speaking, which was seen as a barrier to good Englishness. Walter Rothschild, the Board’s president between 1925 and 1926, demonstrated this opinion clearly in 1912 when he wrote in the Jewish Chronicle – often a mouthpiece for the Board of Deputies at this time – that representatives of the community, in this case a new Chief Rabbi, must be “acquainted with English life and English laws” and be willing to “do all in his power to prevent the teaching and the spread of slang and jargon like Yiddish”. The Board also supported institutions such as the Jewish Free School, with its programme to eliminate Yiddish, which was praised in the Chronicle as a “bridge by which mentally and morally, [the children] may pass from Russia to England.”

Another group with similar goals was the Jewish Lads’ Brigade (JLB), who used cadet-style training as a means of Anglicising the children of immigrants. The notes of its annual reports show that the JLB saw its programme of sport and physical education as a means to “save not only the rising generation, but materially influence generations to come”, believing that only after they had “establish[ed] healthy minds in healthy bodies” could these immigrant boys “become a source of legitimate pride to us”. The implication in this sentiment is that un-Anglicised, these children were a source of shame, not pride. Historian Susan Tanenbaum has even suggested that this language has a eugenic element.

Speaking Yiddish was part of a web of these inferior qualities that needed removing. This is why a 1903 letter from the Victoria Club – a Youth Club similar to the Jewish Lads Brigade – asking for more funding from the Board made the point that, if it was to close, “[q]uite probably 50% of this number [its 200 pupils] would develop criminal propensities.” With the Board’s support, these institutions sought to “iron out the ghetto bend”, or as one speaker put it to the Stepney Club in 1903, to “make the Jews worthy of England”.

Undesirables

Where immigrant Jews proved too difficult to deal with, the Board was happy to support the British government’s deportations. It would be misleading to say the Board never intervened to help potential deportees. The archives, for example, contain correspondence about a group of Jews who had been listed for deportation but then held for periods of up to eight months in Brixton prison in conditions that prevented them from praying. The Board intervened on their behalf regarding conditions and managed to get them released altogether. Yet even a quick scan of the Board’s minutes at the time reveals the selective basis on which interventions were made.

One recorded case notes a man who was charged and then convicted for not registering a change of address, a requirement for all “aliens” in the country from 1919. A deputy “made enquiries at the Home Office [and] gathered that the man was regarded there as an undesirable character.” Because of this, the Board refused to help him. Given the Home Office’s harsh, effectively xenophobic stance towards immigrants at the time, this is a remarkable admission. Another example is the case of Benjamin Zoumerfield, who had dodged conscription and not registered a change of address. The Board supported his deportation because “the man did not appear to have been a satisfactory resident whilst in this country”.

During the First World War, military service, and Jews’ supposed propensity for dodging it, was frequently used as a justification for deportation. This led to the Anglo-Russian military agreement of 1917, which gave immigrant Jews the brutal “choice” between dying for a country in which they had only recently arrived, and which treated them with disdain, or being forcibly deported to fight for the Russian army, and dying for a nation from which they had only just escaped.

The Board's positions over this period were such that when notorious antisemite Williams Evans-Gordon spoke before the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration in 1904, he was able to state: "I put it to you that the Jewish community themselves have been the only restrictionists. It is they who have sent the Jewish people back to these countries." The argument that anti-alien policies couldn’t be antisemitic because they mirrored the actions of the Jewish community’s leaders became one of his stock arguments.

These policies stemmed from a kind of doublethink among the Board’s leaders. To the wider public and the government, they presented Jews as excellent, unfairly-harassed citizens, while also attempting to browbeat a community they considered unsatisfactory into palatable shape. The Board’s archived publications contain titles such as The Jew In The World Today, The Jew As British Citizen, and The Jewish Contribution To Western Civilisation. Little of this grace and praise was dispensed to those applying to the Board for help, who were often the subjects of scrutiny and suspicion, a problem needing to be solved.

Nothing brought this tension out more vividly than the Board’s actions during the rise of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). The Board was weak in opposing Oswald Mosely, not least because, as an upper-class English gentleman, he presented a conundrum to a group who believed that Anglicisation would negate antisemitism. It is perhaps because of this that, prior to 1936, the Board barely discussed British Fascism. Indeed, when the Board’s president Neville Laski mentioned it, he often did so to criticise those in the community supposedly responsible. In his 1939 book Jewish Rights and Jewish Wrongs, Laski lent support to elite voices in the community that laid the blame for British Fascism at the feet of the working-class and immigrant parts of the community, stressing that Jews needed to “tidy up our own house”. In private he was less guarded. In a 1936 letter, he decried “the gangsters of the Community, who… are exploiting the situation in a manner which may well be dangerous to the Community”.

So hated was the Board’s response that it contributed to the establishment of an opposing body, the Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism (JPC). This group was one of the drivers of Laski’s hatred for “gangsters”, and Laski accused it of trying to “assume functions which only the Board was entitled to exercise”. As Nigel Copsey and Daniel Tilles note, this was part of an initial broader “disapproval of working-class Jewish activism and a desire to protect [their] own position”. At the battle of Cable Street, the Board counselled inaction. It was the work of groups like the JPC, including the distribution of thousands of Yiddish leaflets, that was central to the strong Jewish presence that day.

Changing times

In his response to the letter, Rosenberg has demonstrated some of the same strange thinking of his predecessors. “The signatories are now experiencing what I and other senior Board representatives know all too well,” he writes; “that it is remarkably easy to get the media to listen to you in this country if you highlight your Jewish identity while vocally criticising Israel or its government.” Like the Board more than a hundred years ago, Rosenberg is not only opposed to the letter’s contents, but anxious about the image of Jewishness that deputies may create. The representative capacity of these deputies is restricted; instead they must remain in line with Rosenberg and the British government’s position. It is telling that the letter’s signatories were not accused only of misrepresenting the Board, but also of breaching section 2.1.7, an injunction “to not bring the Board into disrepute”.

Other elements of the Board’s history may suggest where this ends. On 24 May 1917, a different letter appeared in The Times, this one written by Board’s then-president, David Alexander, and the president of the Anglo-Jewish Association, Claude Montefiore. It claimed to speak for the Jewish community in opposition to Zionism. The letter caused an outrage, because Alexander had signed it without consulting any of his fellow deputies. Unilaterally, two of the leaders of Anglo-Jewry had decided to speak for the community as a whole, sharing a view that was common among the Anglo-Jewish elite of the time, but opposed to an increasingly popular movement.

One of the clearest outcomes of the 1917 controversy was that, eventually, the old guard died out and a new leadership took over the Board. The Board’s anti-Zionism proved time-limited after its weak response to the BUF had begun to erode its authority. Not since then has an issue so divided the Jewish community as Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians does today.

Growing, if tentative, opposition to Netanyahu’s government may become the ground on which the community again shifts. The Institute for Jewish Policy Research’s data from the summer of 2024 found 76% of British Jews “strongly” or “somewhat” disapprove of Netanyahu, 74% see Israel’s overall situation as “bad” or “very bad” and 52% feel it hasn’t done enough to provide humanitarian aid to Gazans. All of this was from a year ago, since when the situation has only become more dire. Where it would be simply incorrect to say the majority of British Jews directly oppose Israel, the fact that 70% of British Jews think non-Israeli Jews should be free to criticise Israel means the Board’s censorial attitude feels deeply out of step.

As such, the Board’s condemnation of the letter that appeared in the Financial Times has a clear resonance with its past, one it might not like. Though this time he is speaking out against an unauthorised letter, Rosenberg’s refusal to acknowledge the plurality of opinion within the community is more reminiscent of Montefiore and Alexander than anyone else. As the Board attempts to dig itself in, a question is (re-)emerging about the validity of its claim to represent us. It’s time we begin to ask it more directly. ▼

To donate once or monthly, click here.

Author

Ralph Jeffreys is a freelance writer and journalist, currently working at The Fence Magazine.

Sign up for The Pickle and New, From Vashti.

Stay up to date with Vashti.